- Home

- About Us

- Membership

-

Conferences

- Conference 2024 >

-

Proceedings from Past Conferences

>

- Conference 2023 >

- 2022 - Wellbeing, Sustainability and Impact Assessment: towards more integrated policy-making >

- 2021 - Social Impact Assessment >

- 2019 - Climate Change >

- 2018 - Regional Development

- 2016 - Strategic Environmental Assessment

- 2015 - Where to for Impact Assessment?

- 2014 - Transport Infrastructure

- 2013 Fresh Water Management

- 2012 - Mineral Extraction

- Sign up for updates on future conferences

-

Impact Connector

-

Issue #15 Economic methods and Impact Assessment

>

- Economic methods in impact assessment: an introduction

- The Nature of Economic Analysis for Resource Management

- The State-of-the-Art and Prospects: Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services in Environmental Impact Assessment

- Economic impact assessment and regional development: reflections on Queensland mining impacts

- Fonterra’s policy on economic incentives for promoting sustainable farming practices

-

Issue #14 Impact assessment for infrastructure development

>

- Impact assessment for infrastructure development - an introduction

- Place Matters: The importance of geographic assessment of areas of influence in understanding the social effects of large-scale transport investment in Wellington

- Unplanned Consequences? New Zealand's experiment with urban (un)planning and infrastructure implications

- Reflections on infrastructure, Town and Country planning and intimations of SIA in the late 1970s and early 1980s

- SIA guidance for infrastructure and economic development projects

- Scoping in impact assessments for infrastructure projects: Reflections on South African experiences

- Impact Assessment for Pacific Island Infrastructure

-

Issue #13 Health impact assessment: practice issues

>

- Introduction to health impact assessment: practice issues

- International Health Impact Assessment – a personal view

- Use of Health Impact Assessment to develop climate change adaptation plans for health

- An integrated approach to assessing health impacts

- Assessing the health and social impacts of transport policies and projects

- Whither HIA in New Zealand….or just wither?

-

Issue #12 Risk Assessment: Case Studies and Approaches

>

- Introduction

- Risk Assessment and Impact Assessment : A perspective from Victoria, Australia

- The New and Adaptive Paradigm Needed to Manage Rising Coastal Risks

- Reflections on Using Risk Assessments in Understanding Climate Change Adaptation Needs in Te Taitokerau Northland

- Values-Based Impact Assessment and Emergency Management

- Certainty about Communicating Uncertainty: Assessment of Flood Loss and Damage

- Improving Understanding of Rockfall Geohazard Risk in New Zealand

- Normalised New Zealand Natural Disaster Insurance Losses: 1968-2019

- Houston, We Have a Problem - Seamless Integration of Weather and Climate Forecast for Community Resilience

- Innovating with Online Data to Understand Risk and Impact in a Data Poor Environment

-

Impact Connector #11 Climate Change Mitigation, Adaptation, and Impact Assessment: views from the Pacific

>

- Introduction

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation, impact assessment, and decision-making: a Pacific perspective

- Climate adaptation and impact assessment in the Pacific: overview of SPREP-sponsored presentations

- Land and Sea: Integrated Assessment of the Temaiku Land and Urban Development Project in Kiribati

- Strategic Environmental Assessment: Rising to the SDG Challenge

- Coastal Engineering for Climate Change Resilience in Eastern Tongatapu, Tonga

- Climate-induced Migration in the Pacific: The Role of New Zealand

-

Impact Connector #10 Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

>

- Introduction

- Is a “just transition” possible for Māori?

- Adapting to Climate Change on Scale: Addressing the Challenge and Understanding the Impacts of Asia Mega-Cities

- How responding to climate change might affect health, for better or for worse

- Kanuka, Kereru and carbon capture - Assessing the effects of a programme taking a fresh look at the hill and high country land resource

- Wairoa: Community perceptions of increased afforestation

- Te Kākahu Kahukura Ecological Restoration project: A story within a story

- Issue #9 Impacts of Covid-19 >

-

Issue #8 Social Impact Assessment

>

- Challenges for Social Impact Assessment in New Zealand: looking backwards and looking forwards

- Insights from the eighties: early Social Impact Assessment reports on rural community dynamics

- Impact Assessment and the Capitals Framework: A Systems-based Approach to Understanding and Evaluating Wellbeing

- Building resilience in Rural Communities – a focus on mobile population groups

- Assessing the Impacts of a New Cycle Trail: A Fieldnote

- The challenges of a new biodiversity strategy for social impact assessment (SIA)

- “Say goodbye to traffic”? The role of SIA in establishing whether ‘air taxis’ are the logical next step in the evolution of transportation

- Issue #7 Ecological Impact Assessment >

-

Issue #6 Landscape Assessment

>

- Introduction

- Lives and landscapes: who cares, what about, and does it matter?

- Regional Landscape Inconsistency

- Landscape management in the new world order

- Landscape assessment and the Environment Court

- Natural character assessments and provisions in a coastal environment

- The Assessment and Management of Amenity

- The rise of the THIMBY

- Landscape - Is there a common understanding of the Common?

- Issue #5 Cultural Impact Assessment >

- Issue #4 Marine Environment >

- Issue #3 Strategic Environmental Assessment

- Issue #2

- Issue #1

-

Issue #15 Economic methods and Impact Assessment

>

-

Resources

- Webinars

- IAIA Resources

- United Nations Guidance

- Donors Guidelines and Principles

- Oceania and the Pacific

- Natural Systems >

- Social Impact Assessment

- Health Impact Assessment >

- Cumulative Impact Assessment

- Community and Stakeholder Engagement

- Indigenous Peoples

- Climate Change and Disaster Risk Resilience >

- Urban Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Strategic Environmental Assessment

- Regulatory Impact Assessment

- Methods in Impact Assessment

- Community

- 2024 Calendar Year Membership Subscription Renewal

Now is the time for a rethinking of, and recovery strategy for, New Zealand’s tourism sector. Our international borders are closed and are likely to remain so for a considerable period, perhaps until early 2022 when a Covid vaccine is established, tested, distributed and administered. For the shorter term we can note that New Zealanders have historically been great travellers both ‘at home’ and internationally. The pressing challenge is to determine how we might refine products and regions for domestic travel patterns that might emerge in a post Covid environment while at the same time supporting regional communities that have become dependent on visitors for their economic wellbeing.

The nature of tourism activity in New Zealand

Over the past few decades, New Zealand has done remarkably well from tourism. Visitor arrivals have doubled every 10.5 years or so since the arrival of jet engine passenger aircraft in the late 1950s. New Zealand, with its outstanding scenery, friendly people and generally well presented environment had risen to be a global favourite to the extent that for the last few years, tourism has been our highest ranked foreign exchange earner (20.4%) and has directly and indirectly contributed to 9.8 percent of GDP (NZ Tourism Satellite Account 2018; StatsNZ).

Coronavirus – a most unwelcome hitchhiker

Tourism has always been vulnerable to a viral attack of this nature and this has been recognised in the scientific literature. Writing seven years ago from Germany, German academics (Brockmann and Helbing) studying H1N1 (2009) and SARS (2003) demonstrated that ‘connectedness not distance predicts the spread of a pandemic’ (Science 12 Dec, 2013).

Coronavirus has achieved its world distribution primarily via aviation routes. Through tourism and trade, global populations have become interconnected to the extent that the models of the pandemic spread run parallel with international aviation routes. At this time the majority of cases in New Zealand can be traced to international arrivals: both ‘tourists’ and returning New Zealand travellers. We have seen how easily the virus is transmitted within New Zealand in what is known as community transmission.

The nightly screening on television of the John Hopkins University’s global cases map strikes a remarkable parallel with international aviation routes such as those that can be generated on google maps. This is not a slight against the management of airports or aeroplanes, which have undoubtedly stepped up their processes and hygiene since SARS, but rather a comment on the ecology of this particular disease.

Cruising appears to be currently bearing the brunt of negative press and imaging. Cruising has had its fair share of critics of its environmental and social performance but the coronavirus risks, which are seen as personal, immediate and urgent may well spell the demise of much of the passenger demand for this mode of transport.

Coronavirus has achieved its world distribution primarily via aviation routes. Through tourism and trade, global populations have become interconnected to the extent that the models of the pandemic spread run parallel with international aviation routes. At this time the majority of cases in New Zealand can be traced to international arrivals: both ‘tourists’ and returning New Zealand travellers. We have seen how easily the virus is transmitted within New Zealand in what is known as community transmission.

The nightly screening on television of the John Hopkins University’s global cases map strikes a remarkable parallel with international aviation routes such as those that can be generated on google maps. This is not a slight against the management of airports or aeroplanes, which have undoubtedly stepped up their processes and hygiene since SARS, but rather a comment on the ecology of this particular disease.

Cruising appears to be currently bearing the brunt of negative press and imaging. Cruising has had its fair share of critics of its environmental and social performance but the coronavirus risks, which are seen as personal, immediate and urgent may well spell the demise of much of the passenger demand for this mode of transport.

But there is more to our tourism than international travellers

While we have been focused on international visitors the less often discussed facts demonstrate that New Zealanders themselves are active travellers. Last year New Zealand residents made 3.0 million overseas trips. Statistics NZ travel data report that within this group, some 78 percent are recognised as leisure travellers (that is, holiday makers and visiting friends and relations). These departing New Zealand leisure travellers therefore generated 2.34 million trips abroad. Of these, some 1.4 million visit Australia, with visitation to the Pacific and Europe contributing much of the remainder. Economist Shamubeel Eaqub reports that according to Stats NZ, New Zealanders spent $6.5b on overseas holidays and business travel last year. This expenditure is deployed to flights, accommodation (less so in visiting friends and relations) meals and other discretionary items (shopping and activities).

A final important dimension of tourist activity is the many thousands of New Zealanders who travel within New Zealand. Kiwi travel patterns can be quite different from our international visitors and hard to measure. The tourism satellite account reports that domestic travellers generate 58 percent of total tourism expenditure within the economy. Domestic travellers undoubtedly display a wide variety of travel behaviours and there is a pressing challenge to determine how we might refine products and regions for them, be they business, visiting family and friends or travelling for other purposes.

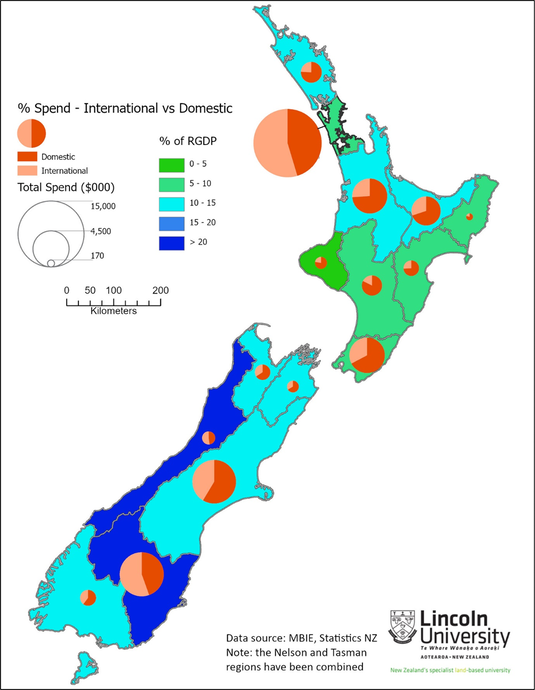

The map below provides a quick visual guide to the extent and impacts of domestic and international tourism expenditure in New Zealand (Data source MBIE : MTRE). The circles represent the proportional amount of national tourist expenditure in each region. Domestic tourists account for more than half of all expenditure in 13 of the 16 regions. The background colours represent a measure of tourism impact simply recorded as tourism expenditure as a proportion of regional GDP. There are three regions with greater international than domestic tourist expenditure. These include the heavily dependent regions of the South Islands’ West Coast and Otago /Queenstown Lakes, which are two of the three regions with greater international than domestic tourist expenditure. Although the West Coast draws only a small proportion of visitor expenditure its ratio to regional GDP is close to 27 percent, and only 3 percent behind Otago /Queenstown Lakes.

A final important dimension of tourist activity is the many thousands of New Zealanders who travel within New Zealand. Kiwi travel patterns can be quite different from our international visitors and hard to measure. The tourism satellite account reports that domestic travellers generate 58 percent of total tourism expenditure within the economy. Domestic travellers undoubtedly display a wide variety of travel behaviours and there is a pressing challenge to determine how we might refine products and regions for them, be they business, visiting family and friends or travelling for other purposes.

The map below provides a quick visual guide to the extent and impacts of domestic and international tourism expenditure in New Zealand (Data source MBIE : MTRE). The circles represent the proportional amount of national tourist expenditure in each region. Domestic tourists account for more than half of all expenditure in 13 of the 16 regions. The background colours represent a measure of tourism impact simply recorded as tourism expenditure as a proportion of regional GDP. There are three regions with greater international than domestic tourist expenditure. These include the heavily dependent regions of the South Islands’ West Coast and Otago /Queenstown Lakes, which are two of the three regions with greater international than domestic tourist expenditure. Although the West Coast draws only a small proportion of visitor expenditure its ratio to regional GDP is close to 27 percent, and only 3 percent behind Otago /Queenstown Lakes.

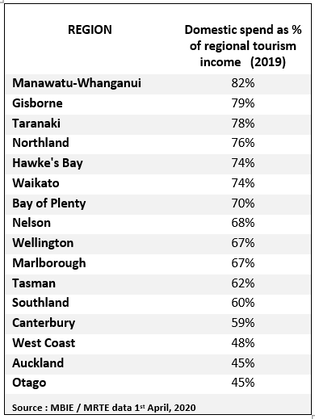

What is not apparent in the map is the significance of domestic tourist expenditure across the regions, which is presented in the table below. Domestic traveller expenditure has some marked differences from international – a smaller proportion is spent on accommodation and hospitality services and a larger proportion on retail shopping, which suggest a one for one substitution is not easily made.

The question is, does domestic travel and displaced international travel by New Zealanders offer a holdfast of hope as we emerge from the strangle hold of the Covid-19 virus lockdown?

Shaking (and shaking) off the virus

Countries differ in their interpretations and ability to respond to the outbreak. China, then Singapore and Taiwan responded early and hard to the Covid-19 with tracking, testing and isolation measures. New Zealand fortuitously has followed suit, but as a well-connected country saw a fairly rapid onset of Covid-19 based on its degree of aviation connectivity and internal mobility.

Global models indicate the continuous spread of the disease to less well connected countries – India, Bangladesh, parts of Africa – at the same time as developed countries / destinations struggle to manage their cases. The model therefore shows a continuous rolling outbreak of ‘hotspots’ across the globe. As a result, we are likely to face an extended period of travel restrictions and an associated absence of international visitors.

Questions then arise, when will it end, or be brought under control, and what will the effects be?

And, for New Zealand and its tourism sector the key question is: If we were to achieve the Governments goal and become a Covid-19 free island state, under what conditions would we allow any visitors (potential new vectors) into our country?

This is a difficult question to face here as visitors are not a homogenous group. Amongst the 3.87 million arrivals are business people, foreign leaders and diplomats, those who are desperate to visit family and friends, seasonal workers (230,000), international students (65,000), and holiday makers. Would we need to provide quarantine facilities for some of these (students) or isolation facilities (business and political travellers, and seasonal workers)? Whatever the solutions, the risks associated with a broad travel market are almost too large to comprehend at the present.

Epidemiologists constantly remind us that a full vaccine (as opposed to shorter acting antimicrobial) passing through all the development and human testing safety analyses is still 12 month away , and then global production and sufficient inoculation is a further 12 – 15 months away. Given this logic, it is entirely possible that New Zealand will not be in a position to welcome back international visitors to March or June 2022. We must think through these circumstances now.

Global models indicate the continuous spread of the disease to less well connected countries – India, Bangladesh, parts of Africa – at the same time as developed countries / destinations struggle to manage their cases. The model therefore shows a continuous rolling outbreak of ‘hotspots’ across the globe. As a result, we are likely to face an extended period of travel restrictions and an associated absence of international visitors.

Questions then arise, when will it end, or be brought under control, and what will the effects be?

And, for New Zealand and its tourism sector the key question is: If we were to achieve the Governments goal and become a Covid-19 free island state, under what conditions would we allow any visitors (potential new vectors) into our country?

This is a difficult question to face here as visitors are not a homogenous group. Amongst the 3.87 million arrivals are business people, foreign leaders and diplomats, those who are desperate to visit family and friends, seasonal workers (230,000), international students (65,000), and holiday makers. Would we need to provide quarantine facilities for some of these (students) or isolation facilities (business and political travellers, and seasonal workers)? Whatever the solutions, the risks associated with a broad travel market are almost too large to comprehend at the present.

Epidemiologists constantly remind us that a full vaccine (as opposed to shorter acting antimicrobial) passing through all the development and human testing safety analyses is still 12 month away , and then global production and sufficient inoculation is a further 12 – 15 months away. Given this logic, it is entirely possible that New Zealand will not be in a position to welcome back international visitors to March or June 2022. We must think through these circumstances now.

A cautionary note: tourism as an economic activity

While tourism is a powerful global economic and development force, it has its foundations as a ‘luxury’ purchase driven by GDP in tourists’ home countries. The principles also shape our travel patterns. In a period of uncertainty, it is natural that people will remain focused on affairs closer to home. Certainly it is reasonable to assume that loss of / recovery of income will be an early focus as we will be rebuilding our savings and retirement bases. Against these needs, we may have the need to escape, be this local leisure, recreation, or longer excursions and overnight trips. These indicate potential for a slow but growing recovery for the leisure and tourism industries – particularly if they are well attuned to the re-framed needs of New Zealanders. Historical patterns of beach and bush visitation and travelling for its own sake may be early re-emerging patterns as we shift back to lower levels on the pandemic management scale. Understanding these effects and their potential to support both the wellbeing of New Zealanders and tourism dependent regions is a useful challenge on which the sector might focus and impact assessors could assist.

Considerations for a new future

There can be no doubt that demand for tourism will be reshaped significantly, and there are doubts we will ever get back to past travel patterns. For now, demand for all forms of tourism is non-existent. There is potential that new forms of domestic travel will emerge, alongside domestic substitution for overseas travel. There will be time in the months ahead to think how we might reposition international travel and our dependencies on it.

These considerations will be influenced by personal and societal economic status and the public’s perceptions of the future economy. Set against these limitations, there is a long standing love of travel and the New Zealand landscape alongside a heightened need to escape from the confines of quarantine and other constraints in the short term. Research on earthquake recovery noted that there is also a strong sentiment to assist those in need and this could be channelled into helping our neighbours in adjacent regions especially where they have been heavily reliant on their tourism economy.

Interestingly, a key supporting element is likely to be the heavily reinforced norm of physical distance; its close cousin ‘empty spaces’ might also shape future behaviour. House ‘bubbles’ can be contained within a family car, and uncrowded sites appear to align well with the new health norms. Can these become part of a new unique proposition?

Questions to which we might turn our attention are to the reframing and repackaging of regional tourism experiences while retaining options for the longer term re-emergence of international tourism. Fiordland (by car) while it is empty, fancy seeing Queenstown in its summer magnificence, what’s this fuss about the Mackenzie night sky or some of the nation’s fabulous bike trails or great walks? The winterless north, or Hawkes Bay anyone?

The outcomes might not occur organically and need to be thought through. As New Zealanders have largely different travel patterns to international visitors, and a ’do it yourself’ attitude, we may well be back to the eighties with extortions ‘Don’t leave town till you’ve seen the country’. Sector, leaders and advisers, need to act now to prepare businesses and regions for a long recovery ahead with clear strategic direction.

These considerations will be influenced by personal and societal economic status and the public’s perceptions of the future economy. Set against these limitations, there is a long standing love of travel and the New Zealand landscape alongside a heightened need to escape from the confines of quarantine and other constraints in the short term. Research on earthquake recovery noted that there is also a strong sentiment to assist those in need and this could be channelled into helping our neighbours in adjacent regions especially where they have been heavily reliant on their tourism economy.

Interestingly, a key supporting element is likely to be the heavily reinforced norm of physical distance; its close cousin ‘empty spaces’ might also shape future behaviour. House ‘bubbles’ can be contained within a family car, and uncrowded sites appear to align well with the new health norms. Can these become part of a new unique proposition?

Questions to which we might turn our attention are to the reframing and repackaging of regional tourism experiences while retaining options for the longer term re-emergence of international tourism. Fiordland (by car) while it is empty, fancy seeing Queenstown in its summer magnificence, what’s this fuss about the Mackenzie night sky or some of the nation’s fabulous bike trails or great walks? The winterless north, or Hawkes Bay anyone?

The outcomes might not occur organically and need to be thought through. As New Zealanders have largely different travel patterns to international visitors, and a ’do it yourself’ attitude, we may well be back to the eighties with extortions ‘Don’t leave town till you’ve seen the country’. Sector, leaders and advisers, need to act now to prepare businesses and regions for a long recovery ahead with clear strategic direction.

David Simmons can be contacted at [email protected] or 027 224 6663.

NZAIA Incorporated is a registered charity

#CC54658

This website and all its content is SSL Protected.

Privacy Policy

#CC54658

This website and all its content is SSL Protected.

Privacy Policy

- Home

- About Us

- Membership

-

Conferences

- Conference 2024 >

-

Proceedings from Past Conferences

>

- Conference 2023 >

- 2022 - Wellbeing, Sustainability and Impact Assessment: towards more integrated policy-making >

- 2021 - Social Impact Assessment >

- 2019 - Climate Change >

- 2018 - Regional Development

- 2016 - Strategic Environmental Assessment

- 2015 - Where to for Impact Assessment?

- 2014 - Transport Infrastructure

- 2013 Fresh Water Management

- 2012 - Mineral Extraction

- Sign up for updates on future conferences

-

Impact Connector

-

Issue #15 Economic methods and Impact Assessment

>

- Economic methods in impact assessment: an introduction

- The Nature of Economic Analysis for Resource Management

- The State-of-the-Art and Prospects: Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services in Environmental Impact Assessment

- Economic impact assessment and regional development: reflections on Queensland mining impacts

- Fonterra’s policy on economic incentives for promoting sustainable farming practices

-

Issue #14 Impact assessment for infrastructure development

>

- Impact assessment for infrastructure development - an introduction

- Place Matters: The importance of geographic assessment of areas of influence in understanding the social effects of large-scale transport investment in Wellington

- Unplanned Consequences? New Zealand's experiment with urban (un)planning and infrastructure implications

- Reflections on infrastructure, Town and Country planning and intimations of SIA in the late 1970s and early 1980s

- SIA guidance for infrastructure and economic development projects

- Scoping in impact assessments for infrastructure projects: Reflections on South African experiences

- Impact Assessment for Pacific Island Infrastructure

-

Issue #13 Health impact assessment: practice issues

>

- Introduction to health impact assessment: practice issues

- International Health Impact Assessment – a personal view

- Use of Health Impact Assessment to develop climate change adaptation plans for health

- An integrated approach to assessing health impacts

- Assessing the health and social impacts of transport policies and projects

- Whither HIA in New Zealand….or just wither?

-

Issue #12 Risk Assessment: Case Studies and Approaches

>

- Introduction

- Risk Assessment and Impact Assessment : A perspective from Victoria, Australia

- The New and Adaptive Paradigm Needed to Manage Rising Coastal Risks

- Reflections on Using Risk Assessments in Understanding Climate Change Adaptation Needs in Te Taitokerau Northland

- Values-Based Impact Assessment and Emergency Management

- Certainty about Communicating Uncertainty: Assessment of Flood Loss and Damage

- Improving Understanding of Rockfall Geohazard Risk in New Zealand

- Normalised New Zealand Natural Disaster Insurance Losses: 1968-2019

- Houston, We Have a Problem - Seamless Integration of Weather and Climate Forecast for Community Resilience

- Innovating with Online Data to Understand Risk and Impact in a Data Poor Environment

-

Impact Connector #11 Climate Change Mitigation, Adaptation, and Impact Assessment: views from the Pacific

>

- Introduction

- Climate change adaptation and mitigation, impact assessment, and decision-making: a Pacific perspective

- Climate adaptation and impact assessment in the Pacific: overview of SPREP-sponsored presentations

- Land and Sea: Integrated Assessment of the Temaiku Land and Urban Development Project in Kiribati

- Strategic Environmental Assessment: Rising to the SDG Challenge

- Coastal Engineering for Climate Change Resilience in Eastern Tongatapu, Tonga

- Climate-induced Migration in the Pacific: The Role of New Zealand

-

Impact Connector #10 Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

>

- Introduction

- Is a “just transition” possible for Māori?

- Adapting to Climate Change on Scale: Addressing the Challenge and Understanding the Impacts of Asia Mega-Cities

- How responding to climate change might affect health, for better or for worse

- Kanuka, Kereru and carbon capture - Assessing the effects of a programme taking a fresh look at the hill and high country land resource

- Wairoa: Community perceptions of increased afforestation

- Te Kākahu Kahukura Ecological Restoration project: A story within a story

- Issue #9 Impacts of Covid-19 >

-

Issue #8 Social Impact Assessment

>

- Challenges for Social Impact Assessment in New Zealand: looking backwards and looking forwards

- Insights from the eighties: early Social Impact Assessment reports on rural community dynamics

- Impact Assessment and the Capitals Framework: A Systems-based Approach to Understanding and Evaluating Wellbeing

- Building resilience in Rural Communities – a focus on mobile population groups

- Assessing the Impacts of a New Cycle Trail: A Fieldnote

- The challenges of a new biodiversity strategy for social impact assessment (SIA)

- “Say goodbye to traffic”? The role of SIA in establishing whether ‘air taxis’ are the logical next step in the evolution of transportation

- Issue #7 Ecological Impact Assessment >

-

Issue #6 Landscape Assessment

>

- Introduction

- Lives and landscapes: who cares, what about, and does it matter?

- Regional Landscape Inconsistency

- Landscape management in the new world order

- Landscape assessment and the Environment Court

- Natural character assessments and provisions in a coastal environment

- The Assessment and Management of Amenity

- The rise of the THIMBY

- Landscape - Is there a common understanding of the Common?

- Issue #5 Cultural Impact Assessment >

- Issue #4 Marine Environment >

- Issue #3 Strategic Environmental Assessment

- Issue #2

- Issue #1

-

Issue #15 Economic methods and Impact Assessment

>

-

Resources

- Webinars

- IAIA Resources

- United Nations Guidance

- Donors Guidelines and Principles

- Oceania and the Pacific

- Natural Systems >

- Social Impact Assessment

- Health Impact Assessment >

- Cumulative Impact Assessment

- Community and Stakeholder Engagement

- Indigenous Peoples

- Climate Change and Disaster Risk Resilience >

- Urban Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Strategic Environmental Assessment

- Regulatory Impact Assessment

- Methods in Impact Assessment

- Community

- 2024 Calendar Year Membership Subscription Renewal