Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services

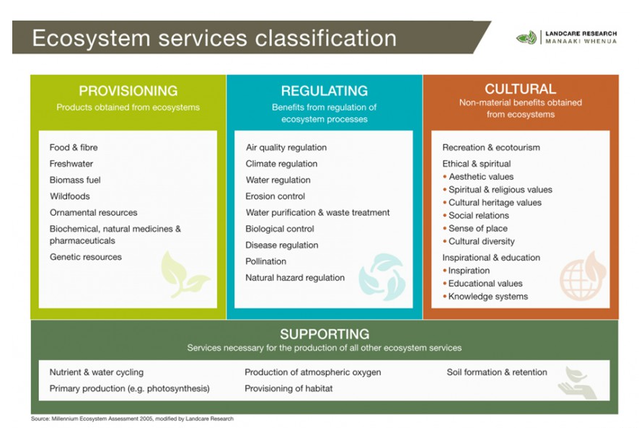

Biodiversity is the variability of life on Earth, from genes to species and their habitats to ecosystems. Living and non-living components interact in ecosystems. In broad terms, ecosystems support us by providing services on which our health, livelihoods, and well-being depend, i.e., water purification and regulation; provision of food, medicine, fiber, and energy; and places for physical, cultural, and spiritual recreation.

People attach a range of values to living things and ecosystems: they can have intrinsic value, use value or cultural value. People are an inseparable part of ecosystems. Although we all rely on these systems for our well-being, poor and vulnerable people often rely directly and most heavily on them for their livelihoods.

Biodiversity assessment aims to identify and adaptively manage the impacts and risks of development in such a way that the variability of life on Earth is maintained in a healthy, functioning and connected state, and the benefits we obtain from ecosystem goods and services will extend into the future. Biodiversity assessment is increasingly striving to achieve a “no net loss,” or preferably, “net positive impact” outcome for biodiversity. Biodiversity assessment recognizes, too, that there are limits to the substitution of services provided by natural systems. It aims to ensure that the costs and benefits of impacts on biodiversity are fairly distributed, striving in particular to avoid increasing the vulnerability of people who are heavily dependent on natural systems for their survival and well-being.

People attach a range of values to living things and ecosystems: they can have intrinsic value, use value or cultural value. People are an inseparable part of ecosystems. Although we all rely on these systems for our well-being, poor and vulnerable people often rely directly and most heavily on them for their livelihoods.

Biodiversity assessment aims to identify and adaptively manage the impacts and risks of development in such a way that the variability of life on Earth is maintained in a healthy, functioning and connected state, and the benefits we obtain from ecosystem goods and services will extend into the future. Biodiversity assessment is increasingly striving to achieve a “no net loss,” or preferably, “net positive impact” outcome for biodiversity. Biodiversity assessment recognizes, too, that there are limits to the substitution of services provided by natural systems. It aims to ensure that the costs and benefits of impacts on biodiversity are fairly distributed, striving in particular to avoid increasing the vulnerability of people who are heavily dependent on natural systems for their survival and well-being.

|

FIVE IMPORTANT THINGS TO KNOW

1. The distribution patterns, threat status, sensitivity and levels of protection—at global and national levels— of ecosystems, habitats, and species affected by development. 2. The objectives, priorities and targets for biodiversity and ecosystem services of official environmental and conservation agencies having jurisdiction in the affected area, and all biodiversity policies or performance standards that must be met by the development proponent. 3. The levels of dependence by local communities on natural resources for livelihoods, health, cultural practices and protection from natural hazards; and trends in the condition or availability of those resources. 4. The limits to what can be lost, harmed, restored and/or off set, taking into account both the irreplaceability and vulnerability of affected biodiversity and the levels of dependence on natural systems by affected human communities. 5. The functional role of the development area in the wider landscape, its buffering role for protected or priority areas, or its role in connecting habitats or ecosystems across climatic or topographical gradients that gives them resilience in the face of climate change. Copied from IAIA Biodiversity Assessment Fastips

|

FIVE IMPORTANT THINGS TO DO

1. Identify major constraints, high risk areas, and significant impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services at the outset, seeking alternatives to avoid them. Only when impacts are unavoidable should measures to minimize, restore, off set biodiversity loss, and compensate for lost ecosystem goods and services be addressed. 2. Use appropriate local specialists with explicit Terms of Reference, and integrate social, economic and biodiversity considerations. Assess indirect, induced and cumulative impacts on biodiversity as well as direct impacts; these impacts are often more harmful than direct or “footprint” impacts. 3. Engage with interested and affected parties—including indigenous peoples—to identify and evaluate impacts and to determine how traditional knowledge and local cultural practices can contribute to any biodiversity initiative. 4. Take a precautionary approach when baseline information is poor, or there is uncertainty about impacts or the effectiveness of mitigation. Good monitoring, research and adaptive responses are crucial for managing impacts on biodiversity. 5. Seek to make a lasting net positive contribution to biodiversity conservation in the affected area through interventions beyond “no net loss.” |

VIDEO: Accessing and interpreting biodiversity information for high-level biodiversity screening